Background

In biology there is currently (to my knowlege) no way to track the position of a certain cell type in the body of an animal live. People often detect the presence of a certain cell via the general method of finding an antibody that attaches to that cell, and then attaching something to the antibody. Much of the time people attach something fluorescent, or something that changes color, or even sometimes a heavy metal to the antibody. This works well once you have extracted the tissue and you want to measure the concentration of the cells.

Idea

Put some heavy-metal attached antibodies into a mouse or other organism. Then bombard the mouse with hella x-rays so that the heavy metal atoms emit their own characteristic x-rays, that are then picked up by a detector. This will give you a signal proportional to the amount of heavy metal atoms in the beam. But it will not of course tell you where the atoms were located. I think using some kind of vision system combined with knowledge about the x-ray beam profile alongside the pose of the mouse should help here. Either the mouse or the x-ray beam need to move around a bunch in order to get good sampling of the location of the atoms within the mouse. I don’t imagine it would be possible to get spatial resolution much better than a mm or two, enough to localise to an organ but not any better than that.

Constraints

The total number of heavy metal atoms in the mouse will be very small since only one (or a few?) atoms will be attached to each antibody, and an antibody has an enormous atomic mass (150e3 atomic mass units). This means that a lead atom with a weight of 207 will comprise 207/150e3 = 0.1% of an antibody already. That’s before you even inject it into the mouse and dilute it again. So it seems very unlikely that there will be enough signal, but I suppose it’s worth figuring it out. If we can find a wavelength of x-ray that water is extremely transparent to but some other element is extremely opaque to, then this might work out I suppose.

Calculations

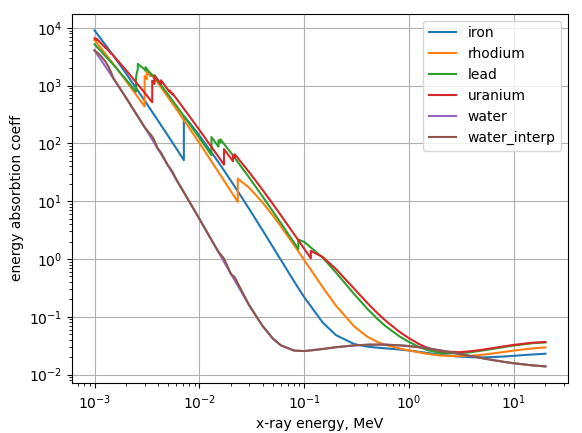

NIST has a great table of x-ray attenuation coefficients as a function of material and of x ray energy. For a given element E we can take the ratio of the element absorbtion spectrum / water absorbtion spectrum, then take the max of that array. If that ratio is something huge like 1e6 then maybe we can say that the mouse is transparent enough to the x-ray and the element is opaque enough that we will get a signal.

Uranium / water

Mice are mostly made out of water, and it seems that the heavier the element the better. So let’s do uranium vs water. Here is a plot of the energy absorbtion coefficients of water an a couple of elements spread over the periodic table:

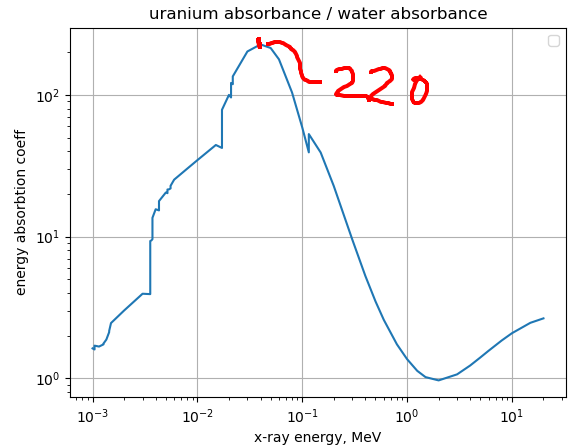

And the ratio of uranium and water:

And the ratio of uranium and water:

How many x-rays to kill a mouse?

Apparently 4-5 Sieverts. A sievert is 1J/kg scaled by some factor. Fortunately for photons, that factor is 1. A mouse weighs about 20g. Let’s say we are using the photon energy of 0.05MeV = 0.05 / 1.60218e-13 = 312e12 photons to kill the mouse.

How many uranium atoms in the mouse?

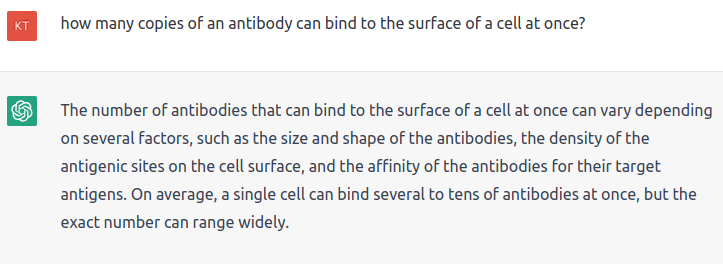

Let’s say there is 1 uranium atom per antibody. How many antibodies can attach to the surface of a b cell?

^This is the best answer I could find. Call it 10. Prolly ChatGPT isn’t that wrong.

Let’s say we want to track B cells. How many B cells are there in a mouse?

Apparently there are about 0.5e9 B cells/L in blood. Let’s say that a mouse has 2ml of blood. So that’s 0.002 * 0.5e9 = 1e6 B cells. Or 1e7 Uranium atoms. Approximating a mouse to be 0% uranium, that’s equivalent to 1e7 * 220 = 2.2e9 water-equivalent atoms (maybe, we might be out by a factor of uranium density / water density here).

If a mouse is all water there is basically 1 mole of water molecules in it, or 6e23 molecules. So that means that 312e12 * (2.2e9 / 6e23) = 1.1 photons will be absorbed by all the uranium in the mouses body in the time it takes to kill the mouse. Don’t you just love it when the numbers work out so neatly?

^This is the best answer I could find. Call it 10. Prolly ChatGPT isn’t that wrong.

Let’s say we want to track B cells. How many B cells are there in a mouse?

Apparently there are about 0.5e9 B cells/L in blood. Let’s say that a mouse has 2ml of blood. So that’s 0.002 * 0.5e9 = 1e6 B cells. Or 1e7 Uranium atoms. Approximating a mouse to be 0% uranium, that’s equivalent to 1e7 * 220 = 2.2e9 water-equivalent atoms (maybe, we might be out by a factor of uranium density / water density here).

If a mouse is all water there is basically 1 mole of water molecules in it, or 6e23 molecules. So that means that 312e12 * (2.2e9 / 6e23) = 1.1 photons will be absorbed by all the uranium in the mouses body in the time it takes to kill the mouse. Don’t you just love it when the numbers work out so neatly?

How many photons would we need?

I don’t really know how to calculate this but I think I can put a reasonable lower bound. Suppose you wanted to detect the concentration of the stuff in the mouse to 0.1mm, and a mouse is 20^(1/3) = 2.7cm on a side. that means a mouse is made from (27/0.1)^3 = 20e6 voxels. You are most definitely going to want to measure a bunch of photons per voxel (it’s not so straightforward to locate a measured photon to a voxel), so it seems unlikely that you could do this with less than 1e8 photons.

Conclusion

1 != 1e8

I guess this explains why people inject many grams of contrast when doing CT scans and suchlike.