I gave up on the fluid simulation on the basis that it wasn’t going to go anywhere even if I could get it to work. The next thing that I want to try is a baby version of alphafold. Instead of the input being the amino acid sequence and hte output being the positions of all of the atoms, the input will be a small molecule SMILES (atomic bonds) and the output will be the positions of the atoms.

Dataset

It seems like the best dataset available for this is the Crystallography Open Database (COD). It has about 500e3 different molecules with their crystal structures determined via x ray diffraction or otherwise. The CIF files it contains have the positions of the atoms an a bunch of other metadata, but importantly they do not have the actual bonds for the molecule in question. So if I want to calculate the 3d positions from the chemical bonds then that rather presents an issue. There is an open source package openbabel that purports to do this and so I ran it against the whole dataset, which took about 10 hours. The dataset contains many things, not just single small molecules with simple bonds. There are ionic compounds, wack compounds, compounds with nobel gasses in them (??), all kinds of stuff. So some exploration and filtering is in order.

Exploration

The quality of this dataset seems to be pretty weird. In addition to this the openbabel tool is highly suspect in its smiles output.

Case study: Urea

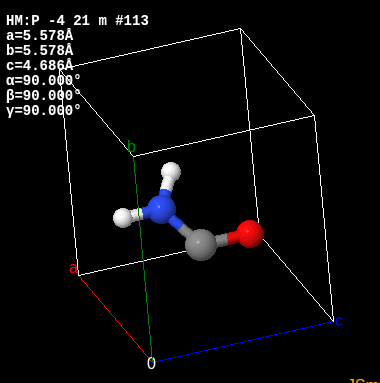

The chemical formula for Urea is C H4 N2 O and it looks like this:

Yet apparently the smiles string for it is

Yet apparently the smiles string for it is O=[C]N which is clearly wrong. In addition to this it’s actually present in the database like 20 times (with the same formula each time). Owait, apparently you can omit the hydrogens. I hate it when chemists be doing that.

Multiple molecule crystals

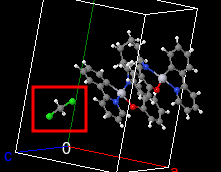

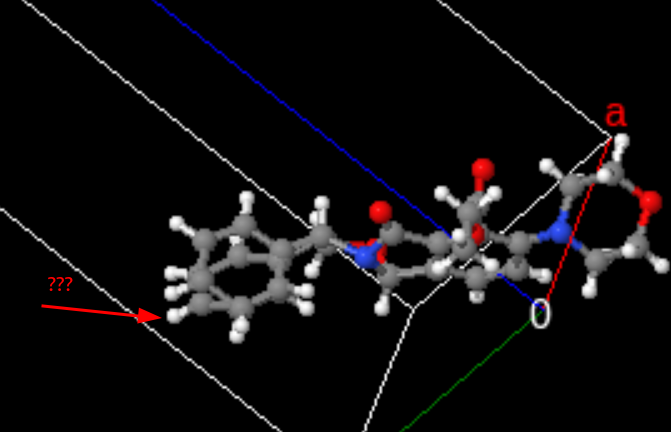

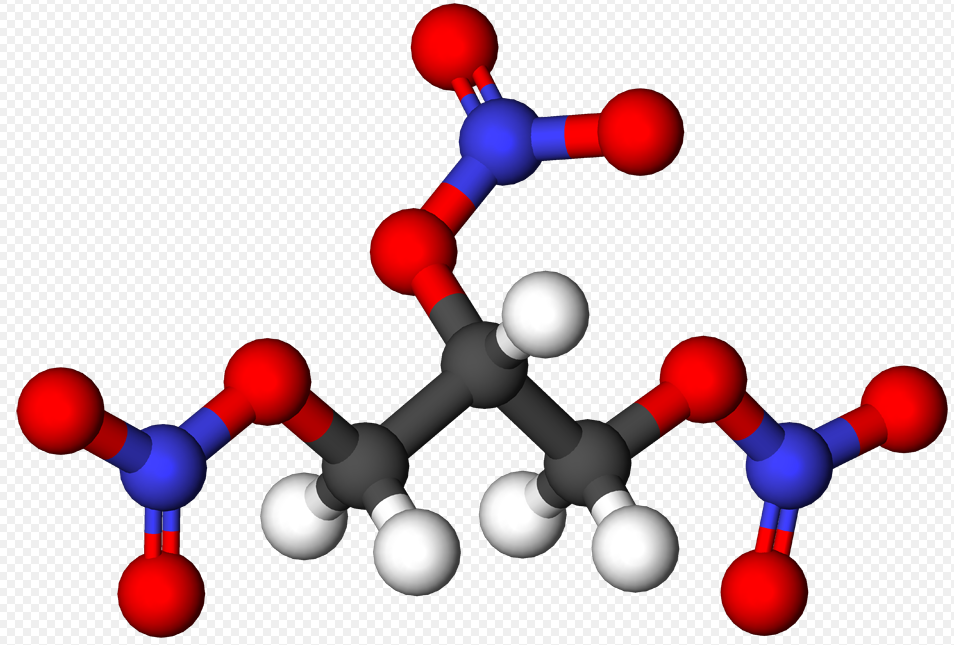

Many crystals contain a few different molecules in their structure, and obvious example being water in all the transition metal salts. There are lots of these in the database like this monstrosity which looks like this:

I think it should be possible to detect this using the SMILES string but it looks like there’s a convention for this in the atomic formula field of the CIF file, a ”,”, like so:

I think it should be possible to detect this using the SMILES string but it looks like there’s a convention for this in the atomic formula field of the CIF file, a ”,”, like so:

C42 H36 N4 O2 Pt2, C H2 Cl2

and so we should be able to detect and reject most of these on that basis.

Not always, though. here is an example where that is not the case. Apparently the smiles string for this is O[C]=O.O, although I have no idea what that means.

Here is a good webpage on smiles strings, and it says that ”.” indicates disconnected structures which does indeed correctly identify the previous crystal as having two bits.

single_molecule_subset = {k: v for k, v in small_subset.items() if '.' not in v['smiles']}Suggests that around 25% of the crystals have more than one molecule in them.

Hydrogen

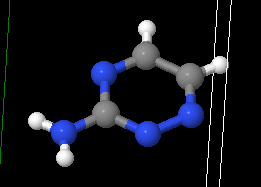

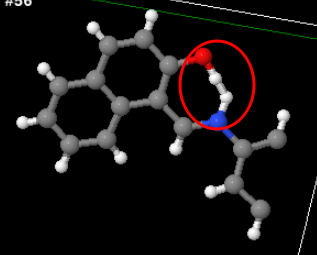

It seems that in a SMILES string hydrogens are optional. The string n1nccnc1N represents this guy:

For example, which is also

For example, which is also C3 H4 N4. I guess since it still has all the information then that’s fine and any neural net will just learn about explicit hydrogens. The xyz position for this particular example contains 11 entries to the hydrogens are present in the output.

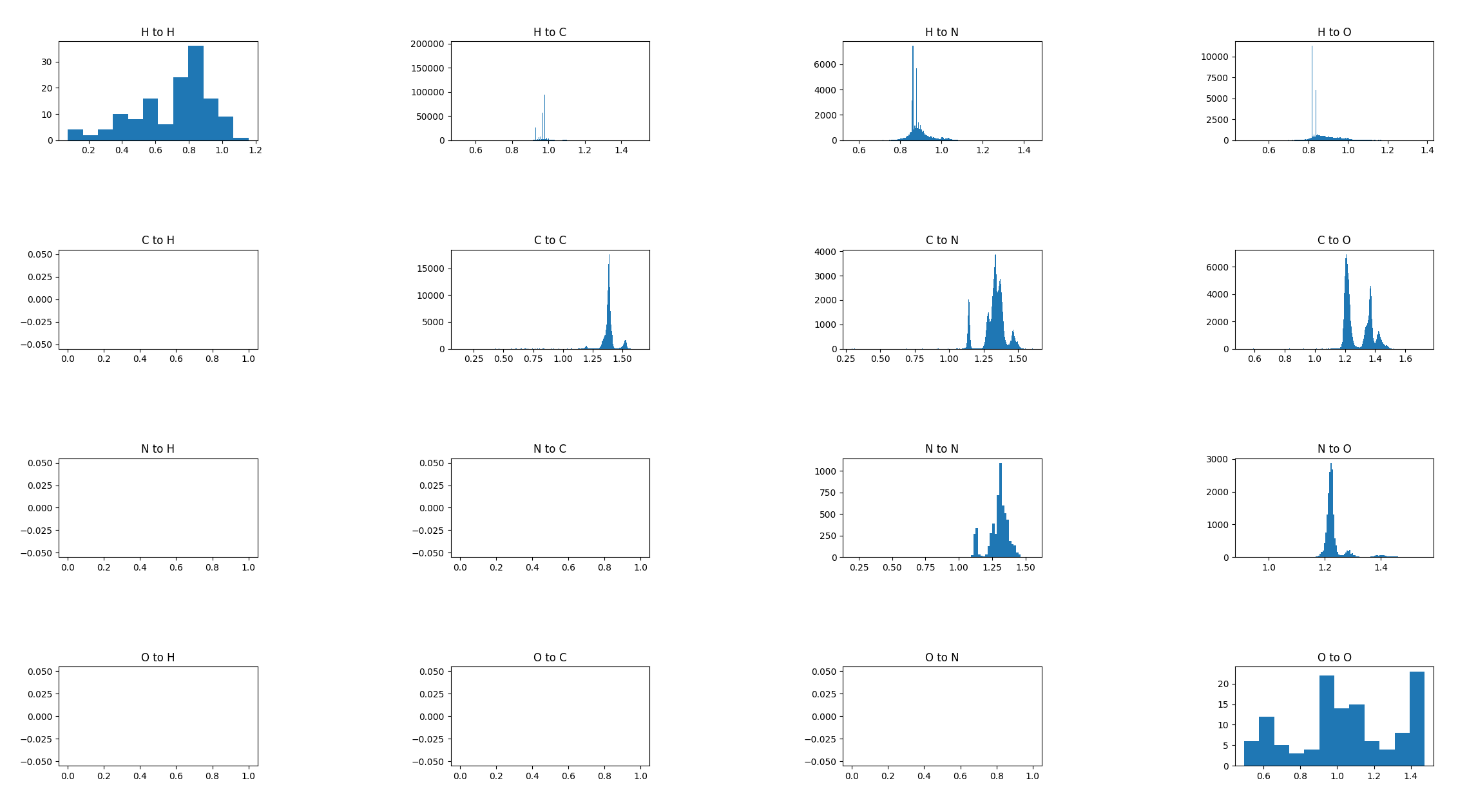

Bond distances

Since the goal here will probably be to generate a distance matrix, exploring the variablility of how close atoms are to other atoms seems like a good idea. Here is a table for all “organic” compounds with >2 atoms showing the closes atom to each other atom:

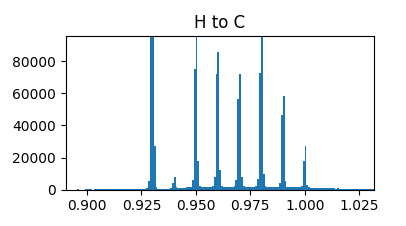

Looks pretty interesting, the nice few-mode distributions all over the place are I presume indicative of double and single bonds and whatnot. There are also a few supposedly impossible things like the H-H bond. The H-C plot doesn’t looks very interesting above but looks like this when you zoom in:

Looks pretty interesting, the nice few-mode distributions all over the place are I presume indicative of double and single bonds and whatnot. There are also a few supposedly impossible things like the H-H bond. The H-C plot doesn’t looks very interesting above but looks like this when you zoom in:

which is pretty cool. X axis is anstroms.

which is pretty cool. X axis is anstroms.

H-H molecule

As an exercise into investigating anomalies, let’s look at those molecules where the closest atom to a hydrogen was another hydrogen.

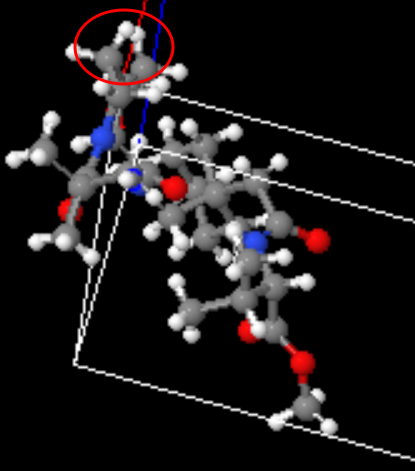

Here is one example of such a compound:

and another:

and another:

and another:

and another:

One final one which juuust might be a real compound:

One final one which juuust might be a real compound:

O-O bonds

Unlike the H-H case, O-O bonds can be legit from peroxides or whatever. But most of the cases in this dataset seem to be garbage, e.g.:

Looks like a nitrite group was duplicated or something there. This one here looks like it might be a nitrate (NO3-):

Looks like a nitrite group was duplicated or something there. This one here looks like it might be a nitrate (NO3-):

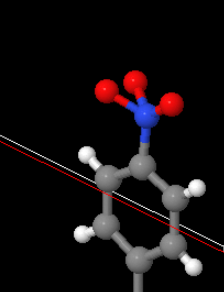

Until you look at a real nitrate and realise that’s not how they be:

Until you look at a real nitrate and realise that’s not how they be:

.

.

What to do.

These errors in the crystallography database are particularly obvious because they are clearly physically impossible. But if there is a high incidence of errors like this then of course that means that errors that are harder to spot are even more prevalent than this, and so this whole database is rather questionable

Possible reasons for discrepancies.

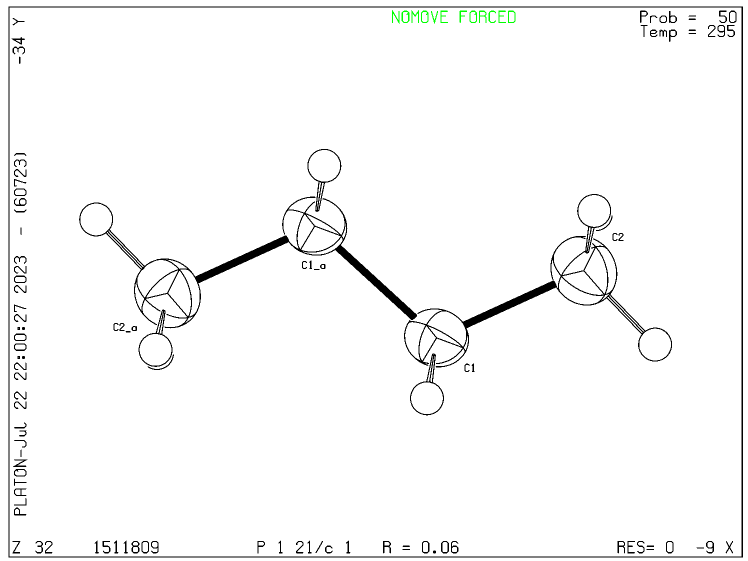

Here is a chemical that you would think is totally impossible to screw up: butane: https://www.crystallography.net/cod/1511809.html and yet it only shows two carbon atoms in the unit cell. I asked chatGPT about it and it had this to say: https://chat.openai.com/share/994735bd-a1eb-4720-a8ea-f77297bc00f8 so it looks like the CIF file format can show just a subset of the molecule and then apply various symmetry operations to define the full molecule. How frustrating. Both openbabel and gemmi do not take this symmetry into account and apply it to get the full molecule out. the CIF file specifies the symmetries that need to be applied to this sub-molecule to obtain the unit cell of the crystal:

_symmetry_equiv_pos_as_xyz

'x, y, z'

'-x, y+1/2, -z+1/2'

'-x, -y, -z'

'x, -y-1/2, z-1/2'

but wait, to get the whole molecule we need to apply only one symmetry but there are 4 applied here! That’s because the unit cell of butane ice apparently is made up of two butane molecules. So which symmetry group needs to be applied to obtain a regular butane molecule?

I did find a CIF checking website online though and for this butane it produces this image:

So it looks like this is possible.

So it looks like this is possible.